Sweden in the Battle Against Plastic – Pioneer or Blind to its Own Problems?

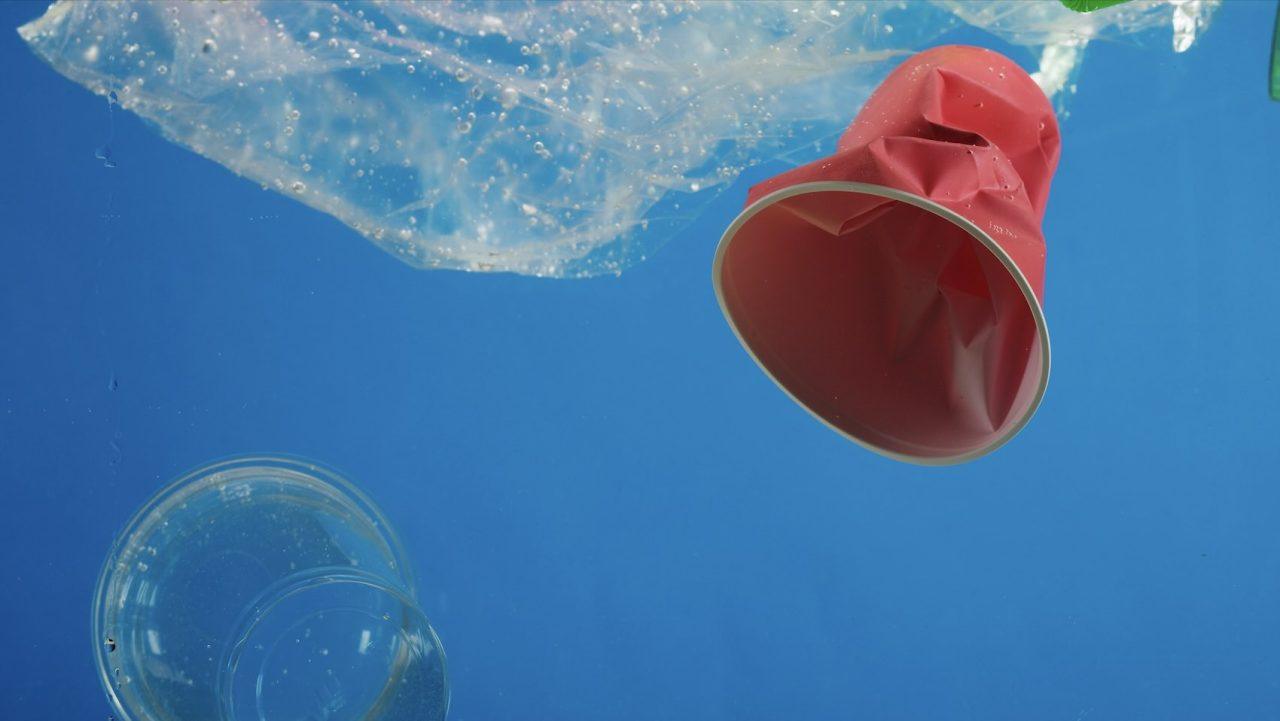

Sweden is praised for its waste management and its commitment to the development of the UN’s global plastics agreement. At the same time, large amounts of plastic are leaking into Swedish waters. Experts warn that plastic emissions – where microplastics, overflow and sewage sludge all contribute to pollution – continue to threaten Swedish aquatic environments.

Text: Fredrik Stedtjer

A global plastics agreement for the oceans

In August, representatives from 175 countries will gather in Geneva to negotiate the world’s first global plastics agreement, led by the UN Environment Programme (UNEP). The goal is to stop plastic pollution at its source by banning or regulating single-use plastics, microplastics, and hard-to-recycle materials, which is expected to have a major impact on the marine environment.

Sweden is part of the High Ambition Coalition, which is pushing for a strong agreement. Nevertheless, large amounts of plastic flow into our oceans and lakes every year.

Leading – but leaking

– Sweden has an advanced waste management system and is ahead of many other countries, says Bethanie Carney Almroth, professor at the University of Gothenburg, who researches the environmental impact of plastic.

However, the plastic that is collected does not disappear from the cycle. Through sewage systems, wind, and rain, it finds its way back into nature. Small fragments, invisible to the eye, are worn away from artificial turf, tires, and textiles. Much of it gets caught in sewage treatment plant filters—but far from all of it.

The plastic that escapes purification continues its journey into waterways and eventually into the sea, where it contributes to plastic pollution and affects animals and ecosystems.

Microplastics – from fields to the sea

A large amount of the plastic that ends up in Swedish seas consists of microplastics. These are worn away in everyday life and carried by rain, sewage, and wind into the sea. In Sweden, tire wear is the largest source, accounting for around 8,000 tons per year. This is followed by artificial turf, synthetic clothing, boat hulls, and industrial waste.

Bethanie Carney Almroth explains that 99 percent of the wastewater that enters treatment plants in Sweden is purified of microplastics, but adds that “we are not solving the problem – we are just moving it around.”

This is because a large proportion of the microplastics captured ends up in sewage sludge – the residual product after treatment. Sludge is then used as fertilizer in agriculture, and the amount spread has increased significantly. From around 30 percent in 2017 to over 50 percent in 2022, according to the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency.

Bethanie Carney Almroth explains that microplastics end up in the soil, where they are stored in sediments. The effects are not yet fully understood, but research points to impacts on plants, insects, and bacterial communities. Ultimately, microplastics can move on—from farmland to our waterways.

At the same time, a government inquiry is underway into a possible ban, similar to those already in place in several countries, including the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, and Switzerland.

Plastic is flushed directly into the sea

During a so-called overflow, sewage systems become overloaded and untreated sewage and wastewater are released directly into the nearest watercourse. This can happen during heavy rainfall or rapid snowmelt, for example. In addition to the risk of spreading disease in bathing and drinking water, plastic waste—such as litter, microplastics, and sanitary waste—also ends up in nature.

“Then you get cotton buds, sanitary towels, everything that people throw in the toilet – we find that waste on the beaches,” says Eva Blidberg, marine litter expert at Keep Sweden Tidy.

Overflows happen regularly, even in municipalities with otherwise well-functioning sewage treatment plants.

Miljöbarometern.se has reviewed the Swedish Water Association’s report, which shows that 30.6 million cubic meters of untreated sewage overflowed in 2023 – more than twice as much as the previous year. That is equivalent to around 12,000 Olympic swimming pools. As climate change progresses, precipitation is expected to increase, making overflows a growing source of plastic pollution in our waters.

This needs to change

One clear action individuals can take is to reduce their consumption of plastic and stop littering. “Behavioral changes are difficult and slow,” says Eva Blidberg from Keep Sweden Clean. She points out that much of the litter on Swedish beaches actually comes from us – Swedes and tourists. This mainly consists of plastic from land that is blown or washed out via storm water and watercourses, as well as fishing equipment that is lost or dumped. Plastic that is not collected slowly breaks down into microplastics and spreads in marine ecosystems with serious consequences for animals and nature.

At the same time, statistics from the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency show that three quarters of Sweden’s plastic waste is incinerated. This is a win for the sea – the plastic does not end up in the water – but it is a loss for the climate.

Incineration does generate energy, but it also releases large amounts of greenhouse gases.

“Incineration can be useful when it comes to plastic containing hazardous substances that we do not want to recycle, but overall it would be better if we recycled more plastic,” says Åsa Stenmarck at the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency.

But focusing solely on waste management is not enough. Bethanie Carney Almroth, professor at the University of Gothenburg, believes that we must reduce both our consumption and new production of plastic. She points out that the life cycle of plastic – from raw material extraction and production, through transport, use and finally waste management – releases pollutants at every stage. Several researchers emphasize that measures must therefore be taken much earlier in the chain, before plastic even becomes a problem in nature.

Åsa Stenmarck explains that microplastics are almost impossible to capture.

“That’s why, for a greater effect, you have to go upstream. Design, production, use – that kind of measures,” she says.

Municipalities bear responsibility – but resources are dwindling

Much of the practical work to combat plastic pollution in the oceans and waterways takes place at the municipal level. Municipalities, together with actors such as the Swedish Transport Administration, spend large sums on cleaning and keeping things clean.

– Municipalities spend 500 million kronor a year on this. This prevents some of the waste from our society from ending up in our waterways,” says Åsa Stenmarck at the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency.

However, according to Eva Blidberg at Keep Sweden Tidy, the funds allocated to municipalities by the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency for beach cleaning have been significantly reduced. She believes that this is a clear sign that the government is not prioritizing the issue sufficiently.

Despite Sweden’s position as a pioneer in the global fight against plastic, there are obvious challenges remaining at home. To really reverse the trend, the plastic problem must be prioritized at the highest level—with political decisions, increased resources, and powerful policy instruments. The message from researchers is clear: municipal efforts and individual willpower are not enough. What is needed are decisions to reduce consumption, improve the design of plastic products, and stop plastic leakage before it reaches our oceans. How Sweden acts now will be crucial for both the environment and the climate—and for Sweden to live up to its role as a global role model on the plastic issue.

About Deep Sea Reporter: Our ambition is to examine and report on issues related to the sea and the life that exists beneath its surface. We operate in the public interest and are independent of political, commercial, and other interests in society.